“I didn’t own a pond, but I wanted to do fish rearing. During a meeting conducted by Ramakrishna Mission in our village, I came to know about a short term course in fisheries. I decided to join it without a second thought,” recalls Chinmoy Mandal, a young fish farmer from Gosaba in West Bengal.

Encouraged by his father, Chinmoy took part in a half-yearly course on pond based farming, which focuses on a scientific approach. ““I learned how to prepare my pond, how to test and treat water, how to cure it using lime, prepare the feed for the fish as well as about netting, growth monitoring etc. and thanks to the training my yield has improved significantly. I knew I wouldn’t be able to make a profit out of fish rearing unless I learned the craft properly. The course proved to be an excellent platform for that,” said Chinmoy.

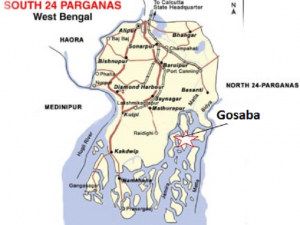

Today, Chinmoy rears fishes in a pond, which he has taken on lease and he is glad that his income has become three times higher than what he earned earlier. Chinmoy is one of the youths trained by Welthungerhilfe’s partner Ramakrishna Mission (Narendrapur) in Gosaba, one of the remotest areas located in the archipelago of Sunderbans, 100 km from Kolkata, West Bengal.

Difficult terrain

Situated on the fringes of the Sunderbans Tiger reserve, the island, surrounded by dense mangrove forests, is ecologically fragile and vulnerable to natural disasters and climate change. Connected with other islands through rivers and with ferries being the only means to move, life in Gosaba is not easy. “People suffer due to poor transport connectivity. Besides, there are no vocational schools or technical colleges here. Boys and girls have to go to Kolkata to acquire higher education,” said Anup Panda, Project head, Gosaba Green College, Ramakrishna Mission, Narendrapur (RKM).

With an aim to improve livelihood opportunities for Gosaba’s youths, Welthungerhilfe has been implementing a programme in partnership with Ramakrishna Mission, Narendrapur and with the support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The aim is to equip the young residents of the area with entrepreneurial skills that can help them find employment or get self-employed. The programme, being implemented since 2013, has been well-received by local residents. “The training is practice oriented,” explained Raju Mondal, who took a course on mobile repairing from the college. “We learned by doing things ourselves at the college and during the course, we got ample opportunities to practice the skills we acquired.” After finishing the course, Raju opened a shop for repairing mobiles. He earns INR 10,000-12,000 a month now, which is almost ten times more than what he had earned earlier.

Raju Mandal runs a mobile repair shop after training

Chiranjit Nath, who was looking for an alternative occupation to farming, found the Green College perfect for learning a new skill. He took a course to become a solar equipment mechanic, a person who is in high demand, considering the area has poor access to electricity. “Most households here do not have a connection to the electricity grid. People nowadays are increasingly using solar operated equipment or lighting systems. But there are very few people who can repair these products. Therefore I took this course and learned it from scratch.” Chiranjit is associated now with a company called Suraj Bandhu, which provides solar equipment related services to customers.

Gosaba Green College provides training in solar technology

Challenges and opportunities

The Green College in Gosaba has provided training to 588 trainees so far. Almost half of them are successfully pursuing their own businesses or are providing services in their villages.

To pursue a course at the Green College, a trainee has to currently pay between INR 1000-2500, depending on the duration of the programme. The money helps cover the operational cost of the college, which is supported by a grant. “Initially people, who were used to getting pro bono training from the governmental or non-governmental organisations, were reluctant to pay any fees, but gradually they understood the benefits of the course and decided to bear the cost, which is nominal,” said Mr Panda of Ramakrishna Mission. He is optimistic that the Green College will continue to skill up people and will be able to sustain on its own soon. “We have established ourselves as a brand. People trust the quality of skill training that the Gosaba Green College provides and with trained entrepreneur spreading the information about our programme through word of mouth, I am sure, we will continue to get new trainees,” he added.

However, at present, the training is attended by those, who can afford the minimal expenses. For the poorest of the poor, bearing the training cost remains a challenge. Therefore, a stronger collaboration among all the stakeholders is needed to bring the programme within the reach of everyone and to ensure its long-term sustainability. One of the possible ways to achieve this is by linking the programme with the government’s ongoing flagship scheme on rural skill development. Green Colleges are therefore envisioned to have a hybrid model of financing where part of the cost is received through course fees while the rest is mobilised through government subsidies in the form of scholarships, projects etc.

Welthungerhilfe has introduced the initiative ‘Green Colleges’, in collaboration with local implementing partners, in Jharkhand, Orissa, West Bengal, Karnataka and Maharashtra. Supported by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), the programme aims to train rural youths in green trades such as sustainable agriculture, animal husbandry, veterinary health, food processing and solar technology and help them develop their entrepreneurial skills. 36,000 rural youth are expected to receive training from Green Colleges till 2019.

*Inputs from RKM, Narendrapur

Farm to Systems – Where is our measuring tape?

Women ‘Ecopreneurs’ felicitated